One Farm Bureau family’s story of overcoming tragedy and beginning a new chapter with honest conversations about mental well-being.

From the summer 2024 issue of Oklahoma Country magazine

Story and photos by Dustin Mielke

With cows to milk, fields to work, hay to bale and chores to be done as a family, Whitney Lawson loved growing up on her family’s farm.

As a child, Whitney was the fifth generation to live on her family’s bustling Canadian County farm, which was settled in the land run of 1889 near the central Oklahoma town of Yukon. From a young age, she would accompany her father, Paul, around the family farm helping with the daily work required to keep the 400-cow dairy, field crop and angus beef cattle enterprises of the operation each moving forward.

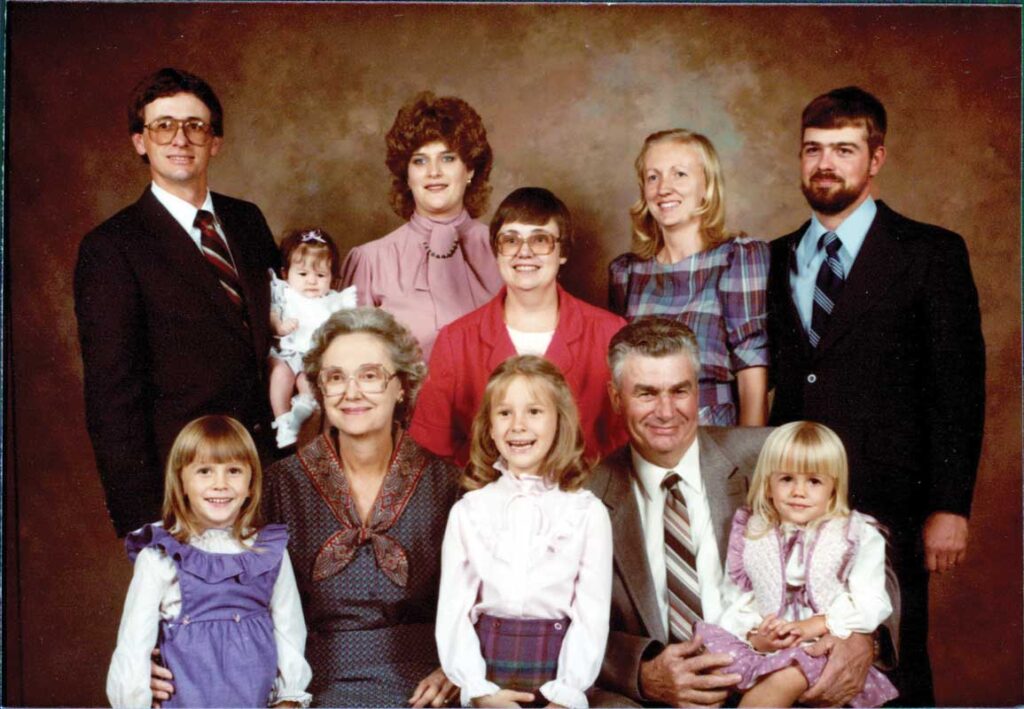

The farm was a family affair that included Whitney’s parents, Paul and Shan, along with her sister; her grandfather and grandmother; her aunt, uncle and cousins; and two other families who lived on the farm full-time. Everyone pitched in, helped out and worked together.

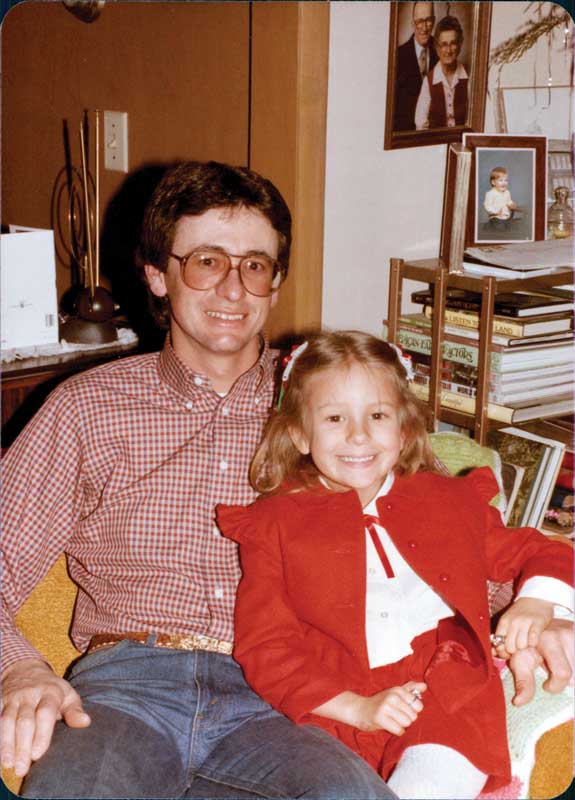

“I loved my dad, we were very close,” Whitney said. “I knew even as a little girl that he was very smart and people were drawn to him and looked to him to take the lead. He had a subtle sense of humor and a strong commitment to his faith.”

said her dad was not only a hardworking farmer who studied every facet of the operation, but he was also an agricultural innovator who took time to help fellow farmers and ranchers both in their local, tight-knit agricultural community and around the state.

“My dad was very involved in helping other farmers be profitable and successful,” Whitney said. “He had a real passion for the community and was very extroverted.”

A graduate of Oklahoma State University with a degree in agriculture, Paul’s passion for continuous learning – and sharing that knowledge with others – was shared with Whitney, who earned a master’s degree in business, and her sister, who earned her medical degree and is now a dermatologist.

Whitney said her dad partnered with OSU extension to help conduct a program where he would travel to meet fellow farmers and analyze their records and financial information to help them find solutions to optimize their farms.

An active Farm Bureau family, Paul and Shan helped with local Farm Bureau events with Paul serving as a county Farm Bureau board member in addition to their involvement with the Associated Milk Producers cooperative.

Whitney said Paul’s innovations on the farm drove him to update equipment that could help the family be more productive. Paul was also a pilot who used his airplane to pick up milking machine parts with increased speed, limiting downtime on the farm.

Fellow Canadian County farmer and Farm Bureau member Henry Heinrich knew Paul, and the pair participated in Farm Bureau events together, including a memorable Young Farmers and Ranchers conference across the state to which Paul flew them.

“He was always helpful and upbeat, and he was just a good neighbor and a good friend,” Heinrich said. “He was one of those guys you could count on.”

“We had an amazing life on the farm,” Whitney said of her early years spent following her dad around the milking barn, the fields and even to the sale barn where Whitney recalls attending cattle sales in pajamas and boots alongside her father.

“He was very innovative, he was ahead of his time, and he was a helper.”

Whitney and her father, Paul

With the farm booming, the family active and engaged in the agriculture community and Paul busy helping fellow farmers while keeping his own operation growing, the Lawsons ushered in the 1990s as a busy and dedicated farm family.

The family’s future, however, was indelibly changed when Whitney was 11 years old.

On Sept. 8, 1990, Paul Lawson died of suicide at the age of 36.

His death came as a shock to his family, the local community and fellow farmers.

“It was really such a surprise to the community,” Whitney said. “You would hear – and I still hear people to say to this day – ‘I just never would have expected a guy like Paul. Paul seemed so happy, Paul was so involved, Paul was so visible.’

“He really was a man that was committed to growing the business and growing the community. When he took his own life, it was a total shock.”

“It hit me pretty hard,” Heinrich said of Paul’s death.

“I never would have imagined that he would resort to that. He always seemed upbeat, but it just struck me that if it can happen to him, it can happen to anybody. I told people back when it happened that of all the people that I knew, he would be one of the last people I could ever imagine would take their own life.”

Whitney said that after her dad’s death, life on the farm changed drastically.

“This place just went quiet,” she said. “It went quiet.

“That was the year that turned the farm upside down. Everything changed after that.”

With Paul gone, the amount of work required to milk the family’s 400 cows while keeping up with the crops and beef cattle was overwhelming. Whitney recalls constant discussion between the family members of what to do with the farm and how the Lawsons could keep up the operation without Paul’s hard work and innovation.

Whitney’s grandfather quickly sold the dairy herd and auctioned off much of the farm equipment. The cropland was leased to neighbors, and after a few years of working to keep up with what remained of the operation, Whitney’s grandfather retired.

Not long after Paul’s death, Shan made what Whitney referred to as a “bold move” to leave life on the farm and move the girls and herself to Oklahoma City to help the family move forward from the tragedy.

“When I think about the healthy steps we’ve taken as a family to move forward, it all traces back to my mother’s bold move to remove us from the situation,” Whitney said. “We really needed a shift in this family to address what was really happening in this family.”

With so many emotions and changes the family has faced from the days immediately following Paul’s death through to today, Whitney said she has leaned on a particular insight her mother taught her:

“My mom shared something with me early when I was a young girl that someone had said to her, which is, ‘When someone takes their own life, they take all the answers with them.’”

The Lawson family circa 1984

In the years since Paul’s death, much has changed in agriculture from integrating technology to improved crops and ever-progressing cattle genetics.

However, the factors that impact the mental health of farm and ranch families are as challenging as ever. From economic pressures to unfavorable weather and from shifting markets to the stresses of running a multigenerational family business, farmers and ranchers still face stresses and challenges each and every day that can put a strain on their mental health and well-being.

The Lawson family has navigated the loss of a father and a husband step-by-step through the past several decades, and they have found themselves serving as a resource, a listening ear and a source of support for other families who have members struggling with mental health and wellness.

Shan, who had earned her master’s degree in social work before Paul’s death, went through grief counseling training and worked more than 35 years as a counselor helping other families achieve a healthier mental well-being.

Whitney said that experiencing the tragedy of her father’s death has impacted her personal approach to mental health, which she said has made her more willing to share her emotions with family and others.

“I practiced being vulnerable from an early age – before the word ‘vulnerable’ became popular,” Whitney said.

“I think being forthright about my experience and not being ashamed of it has really opened a lot of doors for folks to talk to me about feelings and concerns they might not otherwise talk about.”

When Whitney talks to fellow agriculturalists about mental health, she said she shares the need to be open and honest with family members while creating a safe space where everyone can admit that not everything is perfect.

“I think as an agriculture community and the way we are all raised and steeped in our way of life, we just have an extraordinary hurdle to overcome when it comes to taking care of ourselves, both physically and mentally,” Whitney said. “We tend to work ourselves to death and push our bodies beyond their limits.”

She said farm and ranch families need to recognize when they are also pushing their mental health to the limits, even though agriculturalists may not be accustomed to recognizing and acknowledging sources of stress and other factors that can negatively impact mental well-being.

“I would encourage people to treat their mind the same way as we should our bodies

in that we all need to take breaks and we need to give our bodies rest,” she said. “We need to cultivate a similar mental health routine. We have to own the fact that we are a unique group.”

Whitney encourages anyone facing challenges to their mental health to take the first step and reach out to someone even to simply talk through what they are facing.

“Everyone has a resource who feels like a good first step,” she said. “Maybe it’s a minister, maybe it’s a local counselor or maybe it’s just someone with a different perspective.”

As the fifth generation to grow up on the family farm, Whitney is acutely aware of the pressure that is imparted – whether explicitly stated or not – from generation to generation to keep the family farm going. She said that while she feels a deep connection to the farm where four generations before her built a legacy, she and her family have learned to openly discuss the expectations that exist just below the surface along with the desires and needs that each family member brings to the table.

“You can feel connected and intertwined with the land and farming as a passion and as part of your soul, but you do not need to be held to the way that things have always been done,” Whitney said. “You need to be willing to forge your own path and make changes.”

The Lawsons live out this openness through a pact that Whitney said she and her sister maintain to check each other and make sure they are taking on the management and operation of the family farm as something they want to do rather than going through the motions trying to live up to long-held expectations.

As the family continues to navigate life without Paul, Whitney encourages other farm families to take a proactive approach to discussing mental well-being, even if it does not come naturally.

“Please do not let tragedy come to your doorstep to wake up,” Whitney said. “Be the instrument of change and talk about things before they become big things.

“You can have the push, the shove or the two-by-four. My family got the two-by-four. And I don’t want that for anybody else.”

You can feel connected and intertwined with the land and farming as a passion and as part of your soul, but you do not need to be held to the way that things have always been done. You need to be willing to forage your own path and make changes”

The Lawson’s family farm looks quite different today than it did back in 1990, but a flurry of activity and energy has returned to the centennial farm located just southwest of Yukon.

Whitney has returned to the farm after a decades-long career in the pharmaceutical industry, fulfilling a lifelong dream to care for the land that has been in the family for generations.

She and her crews have worked to remove overgrown trees, trim back brush and grass and even remodel the farmhouse. The pastures out back are home to Whitney’s growing herd of American quarter horses, which are trained for their athletic abilities in barrel-racing competitions and ranch work.

“I am passionate about the land, and I believe God has entrusted us with this land,” Whitney said. “I feel called to be a steward of the land and the animals, and I think it’s an amazing way of life. It’s in my soul.”

However, Whitney also recognizes that not everyone in her family feels the way she does about agriculture. And that’s OK.

Whitney said her family communicates openly about the farm and its management. Expectations are clearly laid out with openness and transparency. The family collectively shares an understanding that members can use their land as they deem best. Whitney said it is all part of forging a healthy path forward as a family.

“This is my happy place, and this is my safe space, and I’ve worked really hard to associate it with moving forward,” Whitney said. “This is a way forward for me and my family.”

As a survivor of a family member’s suicide, Whitney said she is still navigating the loss of her father.

“It never stops hurting,” Whitney said. “The best thing a person can do when interacting with a suicide survivor is not to make it weird, and to treat it like any other loss. And avoid the temptation to jump to conclusions because you never know what’s going on behind closed doors.”

As she watched the horses roaming the back pastures and new coats of paint being applied to the farm’s outbuildings on a bright, sunny morning in June, Whitney was witnessing the future of the family farm taking shape. She said that while she endeavors to raise quality equine athletes and care for the natural resources entrusted to her, her hopes for the farm all circle back to helping people

“I want this to be a place that makes people feel good,” Whitney said. “I want this to be a place of community gathering, and hopefully even a source of education at some point. But I mostly want this to be a place that celebrates the beauty of nature, God’s gifts, community and friendships. This is just a place that I hope people want to be.”

Looking for help?

If you or a loved one is experiencing thoughts of suicide, call the national Suicide and Crisis Hotline by dialing 988. The lifeline is a network of local crisis centers that provide free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. If you would like to find a local counselor, counseling services, or other mental health information, American Farm Bureau has a directory of mental health resources on their Farm State of Mind website at www.fb.org/initiative/farm-state-of-mind. Farm State of Mind also features resources for rural and agricultural community members who would like to learn how to assist others facing mental well-being crises.

OKFB’s Cultivating Healthy Minds program

Oklahoma Farm Bureau’s Cultivating Healthy Minds program provides mental health resources through a series of live webinars to help Oklahoma agriculturalists learn how to have discussions about mental well-being in their local communities. Launched in 2023, OKFB will once again host three webinars in

the months of August, September and October featuring personal testimonials and professional presenters discussing mental health and well-being topics targeted toward the agriculture community.

The 2024 program will culminate with an in-person discussion at the OKFB annual meeting in November in Oklahoma City. To learn more about the upcoming webinars, visit OKFB’s website at okfarmbureau.org. To access recordings of last year’s webinars along with additional resources, visit the OKFB website at okfb.news/CHM23.